FAQ

Short fact-checked answers to frequently asked questions about climate and biodiversity. If you don’t find what you’re looking for, reach out to us here.

Can solar variations explain ongoing global warming?

No. These authors showed that the influence of solar variation on global temperature from 1980 to 2010 (0.12 degrees) was far smaller than global warming for the same time interval (0.6 degrees) and in the wrong direction, meaning that solar variation alone would have caused cooling, not warming. That the impact of human-induced global warming far exceeds that of not only solar variation but also volcanic activity is further confirmed by the IPCC in their 6th assessment report. Finally, observations reported by these authors show that warming of the atmosphere is largely restricted to the lower part of the atmosphere - a fingerprint of human-induced warming. Solar variations would be expected to affect not only the lower, but also the upper atmosphere.

Can we cause a mass extinction by burning fossil fuels?

Yes, but only if we carry on. A mass extinction is characterized by the Earth losing more than 75% of its species in a (geologically) short period of time. Mass extinctions have happened five times since the explosion of life 541 million years ago. These authors have shown that, at present, species are going extinct faster than is geologically normal. This is a warning sign of a possible mass extinction. One of the reasons that this is happening is that by burning fossil fuels, we are heating the Earth faster than, and (if we carry on) we will heat the Earth more than the thresholds of temperature change for mass extinctions. This causes the habitats in which species live to move very quickly. These authors show that a rising number of species can’t keep pace with their moving habitats, putting them at risk of extinction.

Can we replace fossil fuels with biofuels and carry on as normal?

No, but they can help a bit. Biofuels are fuels which come mostly from plants. They can provide an alternative to fossil fuels, especially for the transport sector. These authors write that the global warming potential of some (but not all) biofuels is lower than fossil fuels. The IPCC include biofuels among options available now to reduce greenhouse emissions but note that, for transportation, other options (e.g., a shift to public transportation) are considerably cheaper. The aforementioned authors further note that relying on biofuels to reduce emissions comes with other impacts, e.g., acidification, eutrophication, water shortages and biodiversity loss.

Can we just plant more trees and carry on as normal?

No. The Earth isn’t big enough. Protection and restoration of forests has enormous potential as a contributory solution to the climate and biodiversity crisis. These authors calculate a potential of 226 billion tons of carbon storage in areas of existing forests (which could be protected) and regions where forests have been cut down (which could be restored). Although this potential is large, it is less than the 279 billion tons of carbon that we had already added to the atmosphere by 2019. Given that, on top of this, we continue to add, on average, around 11 billion tons of carbon to the atmosphere annually, emissions reductions are still vital.

Does carbon offsetting work?

No. There are 3 categories of solutions to the climate and biodiversity crisis. These are emissions reduction, nature-based solutions (e.g., planting trees, cutting down fewer trees, restoring wetlands) and carbon dioxide removal (e.g., CCS). The IPCC have compared a number of different solution pathways. All of them show that we need to implement all 3 solutions at the same time to achieve net-zero emissions. When we offset our emissions, we replace emissions reductions (one of the solutions) with nature-based solutions (another one of the solutions). This makes no sense because we needed both solutions to solve the climate and biodiversity crisis.

How long have we known that burning fossil fuels is a problem?

Since 1896. Svante Arrhenius made the connection that by burning fossil fuels we would make the Earth warmer, and wrote about it in a paper which was published in 1896.

It was warmer before. Why are worried about a few degrees of global warming?

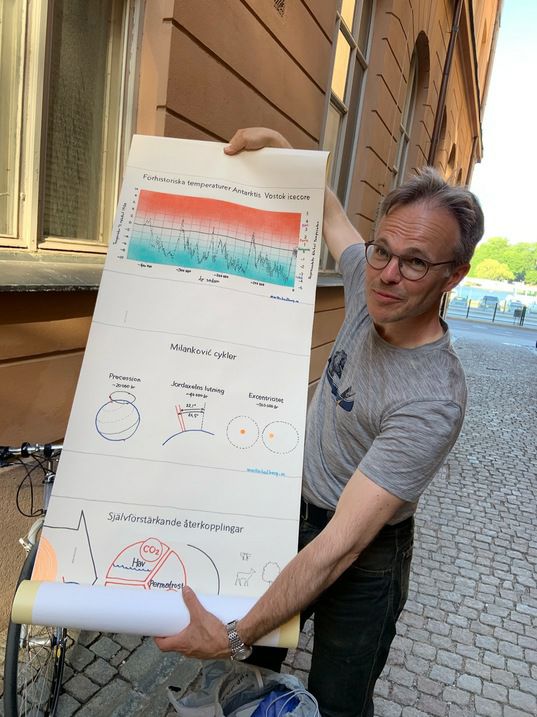

Because it is happening so fast. Climate varies naturally on different timescales. Continental drift causes climate variability on a timescale of millions of years: These authors calculated that the Earth was around 10 degrees warmer 66 million years ago. Since then and at this timescale, Earth has been cooling very slowly (1 degree every 7 million years). This cooling caused the Ice Age, which started 2.6 million years ago and is still ongoing. Cyclical changes of Earth’s orbital path and to its axis of rotation cause climate variability on a timescale of thousands of years. These authors calculate that the Earth was around 7 degrees cooler 24 thousand years ago. Since then and at this timescale, Earth have been warming slowly (1 degree every 3400 years). This warming marks the end of the last glaciation. Global warming, caused by humans is happening much faster. The IPCC report that the Earth has warmed by around 1 degree in 50 years. This is so fast that plants and animals do not have time to adapt, putting them at risk of extinction.

Is solar geoengineering a good idea?

No. There are various kinds of solar geoengineering but they all have one thing in common. Solar geoengineering is about manipulating Earth’s albedo, meaning Earth’s ability to reflect incoming sunlight. A strong albedo effect means that more sunlight is reflected back into space and the Earth becomes cooler. By enhancing Earth’s albedo (with mirrors in space, or reflective particles in the upper atmosphere), we could counteract global warming. This might seem like a good idea, but it’s not. The problem comes when we stop, which will happen sooner or later (because we can’t afford to continue, because our political leaders don’t agree with each other, because we run out of the fossil fuels, we are using to get whatever we are using to reflect sunlight in the upper atmosphere or space). When we stop, the greenhouse effect that we made stronger by adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere will still be there (perhaps it will be even stronger). This is because atmospheric CO2 levels take a very long time to fall. Temperature will rise faster than if we had not deployed solar geoengineering. This is known as termination shock. It will cause the habitats in which species live to move extremely quickly, putting them at risk of extinction.

What’s the problem with burning fossil fuels?

Fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) contain carbon which was captured from the air by living things (plants, plankton, algae) over millions of years. When we burn fossil fuels, we put lots of that carbon back in the air all at once. These authors have shown that no natural process exists that can remove all of that carbon anything like as fast as we are adding it and that a lot of it stays in the air as CO2 (a greenhouse gas). This makes the Earth hotter, causing the climate and biodiversity crisis.

Could aerosols emitted by humans mask human-induced greenhouse warming?

Yes. Aerosols (very small particles) emitted by humans (e.g., when we burn stuff) tend to cool the climate by reflecting some sunlight back into space. However, this effect is short-lived because aerosols only remain in the atmosphere for a short time (a week or so). This can temporarily mask the warming effect of CO2 emitted by humans, which (unlike aerosols) carries on affecting the climate for many hundreds of years. This masking effect is regional because aerosols fall out of the sky fairly quickly. These authors link faster warming in Europe partly to a reduction of this masking effect that was brought about by efforts to reduce aerosols emissions in the region. In contrast, continued emissions of aerosols carry on masking greenhouse warming in eastern China and India. Globally, this masking effect may be hiding an additional 0.5°C of greenhouse warming. However, as these authors have shown, the masking effect of aerosols on greenhouse warming is diminishing. This will, in turn, reveal the true scale of human-induced global warming.

Why is flying a problem?

Carbon dioxide emissions per person are higher for flying than for most other ways of travelling. For example, emissions for one return flight in economy class to southern Europe are, on average, about 1 ton. This is the same as what one person can emit in an entire year if we are to secure a livable and sustainable future for all according to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. From a climate justice perspective, these researchers argue that we need to reach this target within around five years. If you are able to and need to travel, choosing an alternative to flying can be an easy way to reduce your own emissions. You can compare different options here.

Why 1 ton?

According to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, global emissions should average no more than 1 ton of carbon dioxide equivalents per person per year (currently our average emissions are 8 tons per person per year). From a climate justice perspective, these researchers argue that we need to reach this target within around five years. Achieving this “1-ton target” would mean that 8 billion people would emit 8 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalents each year. This equates to 2.2 billion tons of carbon annually. The same amount of carbon is added to and removed from the atmosphere annually by natural processes. Achieving the “1 ton target” would be a vast improvement on the current situation which is that our emissions are five times more than all natural processes added together.

What is carbon dioxide removal (CDR)?

Carbon dioxide removal technologies (CDR) are a package of methods to capture carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and subsequently store it permanently in the bedrock. Two of the more discussed methods are BECCS or bio-CCS (Bio-Energy with Carbon Capture and Storage) and DACS (Direct Air Capture and Storage).

In BECCS, the carbon dioxide is ‘captured’ by trees which later feed industrial processes, through combustion of biomass. The carbon dioxide is captured from the industry flue gas, and thereafter transported to suitable storage sites where the gas (sometimes dissolved in water) is injected into the bedrock for permanent storage.

In DACS, the trees are by-passed, and carbon dioxide is captured directly from the air (atmosphere) and then transported for storage.

How is carbon dioxide permanently stored in the bedrock?

There are two main storage alternatives, offshore or onshore.

Offshore, storage uses existing pore space in old sedimentary rocks a couple of thousand meters below the seafloor. The carbon dioxide is injected under supercritical conditions, where the high pressure makes the gas behave more like a fluid, into a porous rock that has a sealing layer (so called cap rock) on top. The cap rock prevents the carbon dioxide migrating upwards and back into the ocean. This technique has been used since the mid-1990’s by the oil and gas industry, but then for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR). Injecting carbon dioxide enables the oil industry to optimize the recovery of oil from the oil reservoir. These days, old empty oil reservoirs are planned for carbon dioxide storage, and EOR is, in places, still very much a part of industry plans.

Onshore, storage uses rocks that are chemically reactive with carbon dioxide, such as porous volcanic rocks. Here, the carbon dioxide is injected dissolved in water (also as a supercritical gas) into pore spaces a few hundred meters below Earth’s surface. Once injected, the carbon dioxide will react with the volcanic rock to form solid phase carbonate minerals. This type of storage is also called mineral storage or mineral carbonation. This storage technique is ongoing in Iceland since 2014, where carbon dioxide from a geothermal power plant is captured and injected to a depth of 500 meters in the bedrock. It has been demonstrated that >95% of the injected carbon dioxide turns into solid minerals in less than two years and much of the reactions take place already during the first 100 days. The same chemical reactions in offshore rock formations that are much less reactive are estimated to take several thousand years.

Both ways of storing carbon dioxide are considered permanent.